The Nicolay Connection to the American West

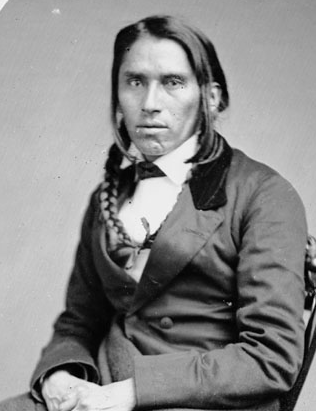

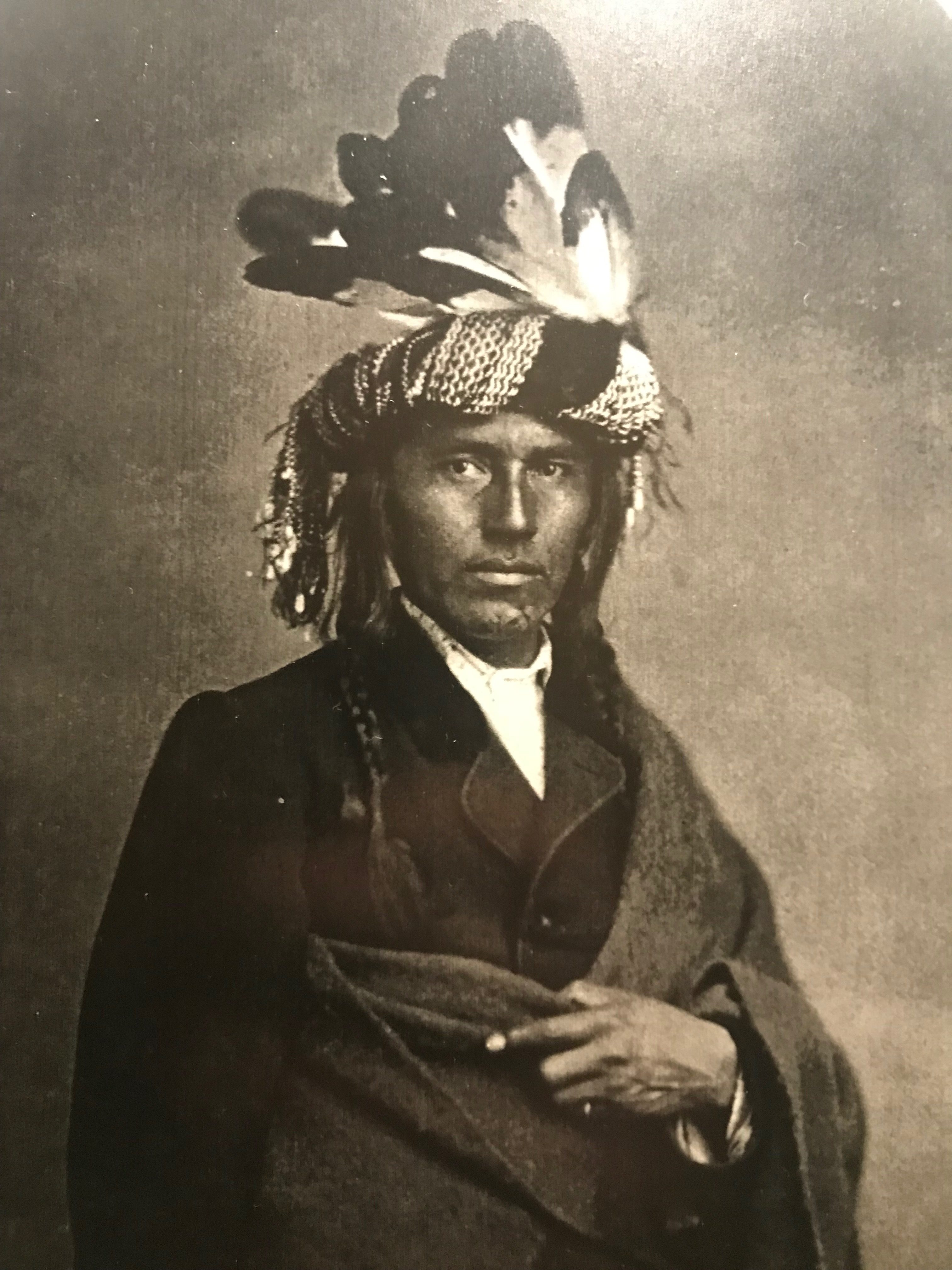

John George Nicolay represents the Lincoln White House in land negotiations with Dakota tribes. Pictured here is Chippewa Chief Hole-in-the-Day whom they met on the banks of the Mississippi in the fall of 1862.

photo from the Smithsonian Institution's National Anthropological Archives

Photo from the Helen Nicolay Collection

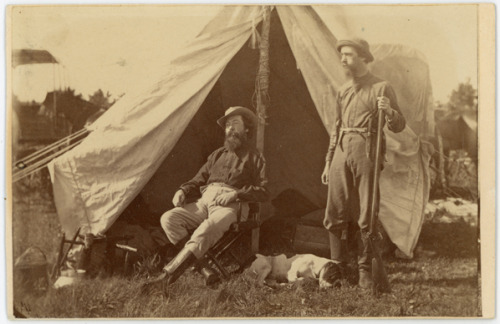

John G. Nicolay stands next to William P. Dole at their campsite in Big Lake, Minnesota, August 24, 1862

Photo taken from The Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection

When John first met Chippewa (Ojibway) Indian Chief Hole-in-the-Day at a tense meeting on the banks of the Mississippi River in Crow Wing, the chief was approximately 40 years old, “but looking very young for that age.”

In the summer of 1862, during the height of the Civil War, President Lincoln sent John Nicolay to Minnesota. He was to meet with William P. Dole, a United States Commissioner of Indian Affairs to help negotiate a land cessation deal with Chippewa (formerly known as Ojibwah/Ojibway) tribes in the Red River Valley. The federal government had already made agreements with the Dakota tribes, the traditional enemies of the Chippewa, in land to their immediate south. This decision would put the Union between the two tribes and would have the benefit of expanding United States federal territory.

John Nicolay was to be an observer and, as personal secretary to President Lincoln, represent the United States federal government in the land treaty. He could not have known the Dakota would wage war against the white settlers, even if he was aware Native Americans were being cheated.

Under the treaty Traverse de Sioux and Mendota in 1851, the Dakota sold their rights to their land to the US Government. They ceded some 21 million acres, in exchange for future payments for a tiny fraction of the land’s worth, equaling approximately $0.07 per acre. They were left with narrow strips of land along the Minnesota River where it was agreed they would settle.

Native American tribes discussed the possibility of going to war with the whites, to take back their land and live as they had before the treaty. Since many men among the settlers left their towns in Minnesota to fight for the Union, some among the Dakota believed it would be the best time to wage war.

James H. Baker, Secretary of State in Minnesota, wrote, “A most frightful insurrection of Indians has broken out along our whole frontier. Men, women, and children are indiscriminately murdered, evidently the result of a deep-laid plan, the attacks being simultaneous along our whole border.”

John Nicolay, William Dole and his group were in St. Cloud, Minnesota when they met Chippewa agent, Lucius C. Walker, who told them of the outbreak. They returned to St. Paul and learned from “a surely and truculent chief of the Mississippi Chippewa,” Hole-in-the-Day, that travel to Fort Abercrombie on the Red River and Fort Ripley were dangerously susceptible to attack.

Hole-in-the-Day tried to entice his fellow tribesmen to join the Dakota in driving the white European settlers out of Minnesota. He was unsuccessful in convincing them, but for a time had motivated some to take action.

At Fort Ripley, Dole sent word to Hole-in-the-Day to engage the chief in a peaceful meeting.

John Nicolay writes, “The Indians are in bad temper and the young braves want to fight; but they are poorly armed and have little ammunition, and therefore hesitate. Hole-in-the-Day is a shrewd and intelligent and able diplomatist, and has the counsel and assistance of interested whites.”

It was not until September 10 that year when they finally arranged to hold council in the village of Crow Wing. The meeting was tense. “At noon the Indians appeared, having crossed at the ferry above the village where the Mississippi sweeps round to the northeast. They came on in irregular, straggling groups, chiefs and braves promiscuously intermingled, not following the road but the bank and the beach of the river.

The Chippewa braves and chiefs ambled down into the village and sat, forming a semi-circle on the upper slope of the village, facing the tents, with the white European settlers and soldiers on the opposite slope. “They were scarcely half seated when two or three of them ran up to the river bank and shouted some signal or command in the direction of down the river,” John Nicolay writes.

Hole-in-the-Day stood, with, “the lower half of the face, from the nose down, painted a deep brown, four of five shades darker than his natural color; a touch of white paint directly under each eye; his long black hair plaited, and the plaits wound horizontally, turban-like, round his head; the scalp-lock, say four inches long, tied so as to stand like a spreading, upturned brush, and painted bright vermillion; and three eagle feathers, slanting backward, fastened in his hair.

“He was dressed in a light, striped shirt, a broadcloth frock-coat, an otter-skin trimmed with red, and evidently used to fasten round the throat like a muffler, hanging back over his shoulder; leggings, moccasins, and a gray blanket gathered and held round the waist with his left arm and hand, so as to leave his right free for gesture in speaking…A black leather belt and holster round his waist held a Colt’s navy revolver, and in his hand he carried a wooden war-club, flat and crescent-shaped, with a large round ball at the end.

“Standing erect, walking, moving his arm, with extended forefinger in emphatic gesture, his eye full of fire, and his features full of expressive energy, while he was making his short speech, Hole-in-the-Day was a very model of wild masculine grace—a real forest-prince.

“But the moment he again seated himself on the ground his muscles relaxed, his eyes closed, his face assumed a look of stupid stolidity, and he was once more a gross, repulsive being, with no higher instinct than hunger, and no higher passion than revenge.”

Despite the casual manner of the speakers and calm formality of the meeting, Nicolay writes it was a “critical and dangerous situation.

“There was no hurry, no confusion, no excitement; a holiday gathering could not have shown more apparent carelessness. Quietly, and with scarce audible commands, the soldiers were instructed and posted in the most advantageous positions for defense.

“Two old backwoodsmen, cool and trusty shots, were stationed within a few paces of Hole-in-the-Day, with orders, at the first signs of conflict, to make him their special mark.”

John Nicolay said that despite the seemingly casualness of the meeting, the Indians were just as prepared for attack. “Sitting and lying about in motley groups, their faces striped and spotted with every imaginable hue and device, their blankets slipping down from their naked, bronzed, sinewy arms and busts, they smoked, chatted, and laughed with each other, feeling of the sharp points of their new, bright arrow-heads, and showing one another the fashion, weight, and convenience of their war-clubs with the most provoking sang froid.”

The Chippewa did not get the amnesty nor ten thousand dollars’ worth of goods Hole-in-the-Day was trying to obtain from the federal government, as John Nicolay wrote. Hole-in-the-Day’s people ultimately revolted against the Chippewa chief’s authority and he was eventually murdered. Hole-in-the-Day was navigating between two different worlds and attempting to find a good middle ground.

Helen writes, “My father entertained no sentimental illusions about the North American Indians. He had grown up too near frontier times in Illinois to regard them as other than cruel and savage enemies whose moral code (granted they had one) was different from that of the whites. Yet he recognized in Hole-In-The-Day a man of strong character and marked ability.”

Nicolay, President Taft and Torrey's Rough Riders

Jay Lynn Torrey

From the Helen Nicolay Collection

A spoon Jay Lynn Torrey gave to his cousin, Helen Nicolay

Helen Nicolay Collection

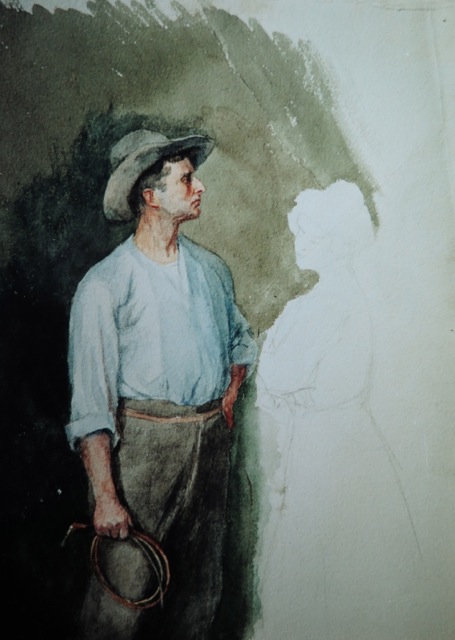

Portrait of a Cowboy, by Helen Nicolay

from the Helen Nicolay Collection

It was June 26, 1898 when Helen Nicolay’s cousin, Col. Jay Linn Torrey, sat in his own room in the headquarters car of a train bound for Florida. Under direction of US President William McKinley, Torrey had mustered together some (300 or more) Missouri men to help the Cubans fight for independence against Spanish armed forces.

Torrey was by this time 46 years old and had lived a full life as an attorney, legislator and businessman. He was born Oct. 16, 1852 to Minerva Lucrecia Norton and Amos Root Torrey in Pittsfield, Il. and grew up in [Louisiana, Missouri] with his family. His grandmother and Helen Nicolay’s maternal grandmother were sisters. Torrey was also a cousin of William Taft, who would later become the 27th President of the United States.

It was February of 1898 when news of the explosion of a United States battleship reached Torrey and fellow Wyoming residents.

The USS Maine, moored in Havana Harbor, Cuba to protect United States interests there during the Cuban rebellion against Spain, sank following an explosion that ripped a hole in its hull. Two hundred and sixty-six, two-thirds of her crew, died from the explosion.

President McKinley appointed a Naval Board to investigate the incident, which determined the explosion had come from a mine originated placed outside the ship. At least, their investigation of the torn, warped steel of the wreckage led them to this conclusion. Other Naval experts later disputed the board’s finding and several believed the explosion had come as a result of spontaneous combustion of bituminous coal stored in the hull that had caused munitions in an adjacent section to explode.

News of the Naval Board’s report to the President spread and it was the “Yellow Press” of William Randolf Hurst and Joseph Pulitzer that accused Spain for the attack on the Maine. Two days after the explosion, one headline in the Hurst-owned New York Journal read, “The Warship Maine Was Split in Two by an Enemy’s Infernal Machine.”

Two months after the Board’s report to President McKinley, on April 20, Congress passed a joint resolution demanding the withdrawal of Spanish armed forces from Cuba. A declaration of war with Spain soon followed.

The prevailing cry, “Remember the Maine. To Hell with Spain,” published broadly in the yellow press worked its way into the actions and attitudes of an American public convinced a serious wrong against the country had occurred and the cause for Cuban independence was just.

The rallying of troops came from all corners of the US that year. Torrey gathered his men to join Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, which comprised not only of experienced cavalry, but also included writers, doctors, lawyers, college students and many others.

Torrey and his fellow Wyoming citizens wasted no time in organizing into “Torrey’s Rough Riders,” 2nd US Volunteer Cavalry. They trained at Fort David A. Russell in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

On May 30, 1898, the War Department appointed Torrey as Colonel, and on June 22, they left Cheyenne by train, bound for Camp Cuba Libre in Jacksonville, Florida.

His appointment was a source of pride for Torrey, who had a spoon crafted especially for his cousin, Helen. The inscriptions on the spoon read, “Your Cousin” with his initials, JLT, and his image surrounded by the words, “Torrey’s Rough Riders.”

The train had stopped in Tupelo, Mississippi for water, loaded with tough frontiersmen and cattle ranchers who were chomping at the bit to get into the fight.

The headquarters car was the last in line on the train and the first to be struck by a second section drawn by an engine that showed no signs of slowing down. The engineer, a man by the last name of Rawls, sustained internal injuries resulting from the collision and was unable to explain the mishap.

A reporter who was on the train with Torrey and his men provided a number of details for the June 30 edition of The Republican.

“I looked out of the window and saw a man waving a handkerchief frantically, but there was no appearance of slowing down on the part of the coming train. In the car at the time were Major Herberd, Surgeon Major Jesurun, Captain Golden, chaplain, and James McGill. We all ran for the door and jumped.

There was a deafening crash and the engine almost disappeared under the headquarters car.”

The report states Torrey was carried some 300 feet among the wreckage of breaking glass and collapsing timbers, some of which had closed around and had crushed his feet. He was thrown from the wreckage of the train car, which “telescoped with the one ahead and went in like a house of cards.”

At least six of his men died in the collision and several were injured. Torrey carried himself around on crutches for months following the accident, but ultimately recovered from his injuries.

He and his men never made it to Cuba. By the time they arrived in Jacksonville on June 28, they were ordered to remain there. Torrey made appeals for he and his men to be included in the Puerto Rican mission, but cavalry were not needed there. Torrey and his Rough Riders remained at Camp Cuba Libre until they were mustered out in October.

He and his men were certainly disappointed, but were recognized by the American public for their willingness to join the fight. The end of the Spanish-American conflict came with the signing of the Treaty at Paris on Dec. 10, 1898.

Torrey returned to Washington, DC, and to Wyoming where he served out the remainder of his term in the State House of Representatives. He subsequently developed patents for improvements to saddle blankets and branding irons following his work managing his brother’s ranch. He continued his work as an attorney and drafted the first bankruptcy law.

In 1900, Torrey was “prominently mentioned” for McKinley as a running mate on the Republican ticket, but was passed over when Theodore Roosevelt accepted the nomination. Had it not been for Roosevelt, Torrey would likely have been the 26th United States President following McKinley’s death from an assassin’s bullets in 1901.

This same year, John George Nicolay lay in his death bed. He lived long enough to inquire about the details of McKinley’s assassination before leaving this physical world for good.

Torrey, unimpeded by disaster and defeat, became a wealthy man. He moved back to Missouri in 1905, where he purchased a sizable tract of land then known as the “White Farm” and added adjoining land to his title to encompass 10,000 acres. Torrey named this vast tract of land “Fruitville,” where he dreamed of creating the ideal economic haven for patriotic, hard working American families.

'Tannenruh' and the Holderness, NH connection

Pictured here is Tolfod Piper, Helen Nicolay's personal driver while she summered in New Hampshire.